The contracting firm — HoweEngineering Projects (India) Pvt Ltd. — contains the core operations of a business called PMC Projects Pvt Ltd.that India’s government alleged in 2014 was being used by billionaire Gautam Adani’s empire to siphon money overseas. Adani denied all wrongdoing and the probe’s findings were dismissed in 2017 by an adjudicating body.

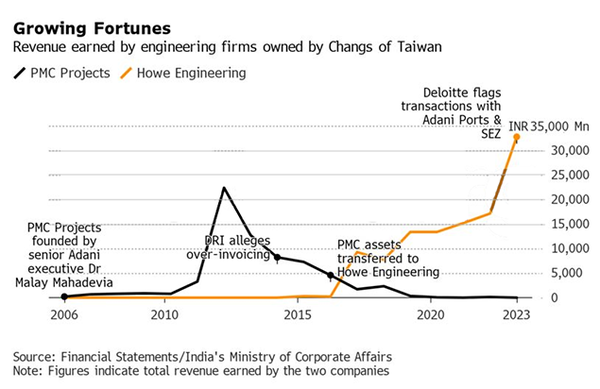

In April 2016, PMC’s engineering business was folded into Howe, according to court filings. Howe has remained an Adani contractor for some of the largest ports and railway lines presently under construction in India, recent filings analyzed by Bloomberg show.

Deloitte’s inability to determine whether Howe should be labeled a related party was why the auditor raised red flags about payments by Adani’s ports company to the contracting firm in May. The accounting giant then resigned as the auditor for Adani Ports & Special Economic Zone Ltd. in August, saying it didn’t have sufficiently wide oversight over the broader conglomerate’s accounts.

Howe puts a spotlight on the challenges shareholders continue to face in understanding how money flows through Adani companies nearly a year after allegations of fraud by short seller Hindenburg Research. Adani has denied all Hindenburg’s allegations. Hindenburg took direct aim at PMC, alleging it was an Adani related party “used to suck money out of the Adani Group’s publicly listed entities.” Its report didn’t mention Howe.

In an email, a spokesperson for the Adani conglomerate said that Howe and PMC are independently operated and managed companies, aren’t Adani related parties and all transactions are compliant with the law. “The commercial and business transactions undertaken by the Adani entities for project management services were entered into in the ordinary course of business at arm’s length basis,” the statement said.

India’s securities regulator has been conducting a probe into Hindenburg’s allegations about Adani. While the agency hasn’t announced its findings yet, it has said that its investigations will examine potential related party transactions among other issues.

PMC Projects and Howe are both owned by an entity registered in Mauritius, which is in turn owned by Taiwanese entrepreneur Chang Chien-ting, filings show. Chang along with his father Chang Chung-ling has had lengthy financial dealings with Adani companies.

When companies identify contractors as related parties during the accounting process, the payments are subject to a much higher level of scrutiny from auditors and the board. However, since Adani has said Howe and PMC aren’t related parties, the group isn’t required to put the Howe payments through these added checks.

Bloomberg visited the office of Hi Lingos Co Ltd., a firm where Chung-ling, the father, is the registered owner in Taiwan. There was only one large logo by the entrance of its office: Adani.

A secretary at the office said that Chung-ling declined to be interviewed. When Bloomberg called a number it was given for the son, the man who answered first asked: “How did you get my number?,” but then went on to say that he wasn’t Chang.

PMC Projects was founded in 2005 by Dr Malay Mahadevia, a long time senior Adani executive, but its ownership was transferred to multiple entities several times over the years. By 2012, its shares had been transferred to the Changs’ PMC Infra Ltd. in Mauritius, filings show. By 2016, the bulk of its business was housed in Howe — the inflection point after which Howe’s revenue shot up.

Bloomberg sent requests for comment to the corporate email addresses of PMC and Howe, but they weren’t answered.

Howe is little known in India and there haven’t been allegations of illegal business dealings involving it. About $450 million of Adani advances to Howe were outstanding as of June, according to the documents analyzed by Bloomberg.

Adani had never publicly disclosed the payments to Howe until Deloitte flagged them in May. About $245 million of refundable deposits was returned by Howe to Adani since then. Contractors typically return these funds once a project is completed or terminated.

“The question is who is getting the money, what work are they doing for Howe and Adani, how is the money being spent?,” asks Sharmila Gopinath, a specialist advisor for India at the Hong Kong-based Asian Corporate Governance Association. “What reason is there not to disclose these payments when there are obviously deep ties with these people, with the owner?”

Crucial Questions

In recent months, Adani stocks have begun to rebound after losing more than $150 billion in market value following Hindenburg’s allegations. The US government, meanwhile, concluded that Hindenburg’s allegations weren’t applicable to the conglomerate’s ports subsidiary before extending the firm as much as $553 million for a container terminal in Sri Lanka, a senior US official recently told Bloomberg.

The group has also drawn new global investments. But some of its stocks still remain off their peak, reflecting the questions still hanging over its sprawling businesses.

Howe’s Ahmedabad offices are housed inside four floors of a glass building that’s a two minute walk away from Adani Groups’ head office within Shantigram, a 600 acre township owned and developed by the conglomerate.

It had annual revenue of 32.8 billion rupees ($390 million) in the last fiscal year, according to its filings. Although Howe has other clients, most of its work is for Adani, according to four people familiar with its operations, who asked not be named because they weren’t authorized to speak to the media. Of the 59 projects listed on Howe’s website, 33 belong to Adani.

The conglomerate provides Howe with funds or advances to manage the construction of its ports, and the money is then passed on to sub-contractors, according to the people familiar with its operations. So, while millions of dollars from Adani’s publicly traded ports business have flowed into Chang’s Howe, where all of it landed remains unclear.

Adani said in its statement that while business and commercial transactions are privileged and cannot be routinely disclosed, they are all “fully compliant with the relevant applicable laws.”

Business groups can’t automatically be assumed to have acted inappropriately, but possible related party transactions “are a risk because there can be abuse,” said Gerhard Schnyder, professor of International Management and Political Economy at Loughborough University in London, speaking broadly on corporate governance.

An Old Hand

The older Chang was a director of Adani Global Ltd. in Mauritius in 1997, and of Adani Global Pte Ltd. in Singapore between 2003 and 2005 alongside Gautam Adani’s older brother Vinod, according to the conglomerate’s public reports.

In 2007, entities controlled by the older Chang owned large blocks of Adani Ports, only to transfer them to entities controlled by Vinod Adani, filings analyzed by Bloomberg show. The father’s entities have also owned shares in other Adani businesses.

In August, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project said in an investigation that the father traded in Adani stock through several offshore entities, pumping up the price in the previous decade and obscuring the true ownership of stock by the group’s founders. The origins of the funds used weren’t clear, OCCRP said.

The Adani Group has refuted OCCRP’s allegations, calling them recycled claims and saying that the expert committee appointed by India’s Supreme Court in March found no evidence of price manipulation in Adani companies’ stocks.

India’s revenue intelligence agency conducted at least three investigations into billing and invoicing at the Adani group between 2014 and 2017. Investigators looked into the relationship between Adani companies and the Taiwanese father-son duo at the time, according to a person familiar with the government probes, who asked not to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak to the media.

In a 2014 show cause notice, investigators alleged that Adani companies imported power equipment and other hardware from manufacturers in South Korea and China through Chang’s PMC Projects and Electrogen Infra FZE Ltd, a Dubai-based entity ultimately owned by Vinod Adani. They alleged that the invoices used for payments by PMC Projects to Electrogen were inflated, allowing funds from Adani companies to be siphoned abroad.

The Adani Group was cleared of all the allegations made against it in 2017 by an adjudicating authority of the agency and later by a customs tribunal. Investigators at the revenue department tried to mount another legal challenge, but India’s Supreme Court dismissed the case, saying that there was no need for interference and upheld the findings of the adjudicating body.

Big Business

Although Adani has said Howe isn’t a connected entity, Gopinath, the governance expert, says that since Adani was paying the contractor large sums of money and its Taiwanese associates were the ultimate owners of the firm, the transactions should have been declared as related party transactions.

Some of India’s rules on the subject can be open to interpretation. For instance, transactions must be disclosed as related party payments when one party has the ability to control or exercise significant influence over the other by participating in its financial and operation decisions.

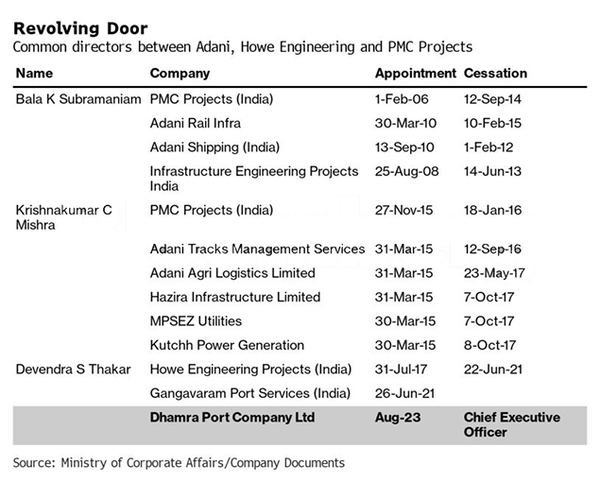

Accounting experts interviewed by Bloomberg also said that if there is a transfer of resources, shared employees or if directors are appointed to specifically to oversee common projects then they should be seen as related parties and payments to them should be subject to added scrutiny from the board and auditors.

Beyond the big contracts flowing from Adani to Howe and PMC, there has also been a revolving door of employees between the three firms, filings show. Past directors at Howe and PMC were also appointed to the boards of Adani group companies over the years.

“The physical proximity of offices (a standard trade practice in such contracts) or the mere holding of directorship – that too, 17 to 26 years ago – will not make the queried transactions related party transactions,” Adani said in its statement.

Gopinath said more scrutiny is needed across India to assess payments by listed companies because investor money is involved.

“We need to tinker with related party transaction regulations because this has opened up a new can of worms,” she said about the debate around Adani’s disclosures.